LinkedIn is one of those products that a lot of people hate, but can’t leave because everybody else uses it.

I can’t believe a product as clunky as Linkedin exists in 2020, but this mail is not about bashing LinkedIn , it’s about one of the key reasons why LinkedIn survived its early days and is successful now: email invitations.

Currently, LinkedIn has 690mn users and garnered $6.8bn in revenue last year. But this success did not happen overnight. In fact, it took 17 years to reach this stage.

LinkedIn in its first month had only 4,500 users and some days had just 20 sign-ups. Just like every other company, the founders and early team relied on their personal network for initial users. 13 people associated with the company invited 112 people.

Reid Hoffman, one of Linkedin’s co-founders, was part of the founding team of Paypal and was a prolific angel investor by that time and he invited some of his most successful friends and connections to join the early product. This ensured that LinkedIn was an aspirational brand, but it did not solve the problem of growth. Brand building while it has its advantages, mostly provides results in a long-term and almost negligible short-term benefit.

Note that this is 2004 when LinkedIn didn’t want to weaken its network by allowing public profiles (or by allowing anyone to connect without email invites or 2nd-degree connection). So traditional growth channels like SEO were unavailable to them then.

So they looked to email and launched their email invitations program which set LinkedIn on a growth trajectory from which it has not looked back.

Fundamentally, it allowed people to uploaded their email contacts and invite them to join their network on LinkedIn.

But isn’t this what every company does? What’s so special about it?

Early mover

For starters, this was in 2004. Not every company did email invitations. So people didn’t mind keeping that option checked in.

Growth hacks by definition are hacks that work within a specific context. Something which works keeps on getting overused by every company until it stops being effective. Then the quest for the next growth hack begins.

Luckily for LinkedIn, they were one of the early movers of this strategy (though not the only one).

Expiry of invitations

Second, these invitations expired within 2 weeks. What it basically solved for, was the invitation acceptance rates.

A typical referral funnel :

No of users signing up -> No of invitations sent -> No of invitations accepted

While a lot of companies focus on the first part of the funnel (number of invitations sent by signed-up users), very few actually try to optimize the second part (Acceptance rate). By putting an expiration date, LinkedIn tried to instigate a sense of urgency into the users receiving them.

Focus on Outlook

Another aspect of their referral strategy was the focus they put on Outlook as compared to webmail contacts.

While many social networks of the time allowed people to invite via email, most of them exclusively focused on webmail and ignored Outlook. But Outlook users completely overlapped with the target audience that LinkedIn was going after.

According to Keith Rabbois (an early employee at LinkedIn), “LinkedIn also deployed an Outlook contact uploader (very painful to build/support) to allow viral spread among professionals. Even today, nobody else has invested energy in this direction despite the 5-10x distribution per inviter you get from Outlook v. Webmail”

Instead of thinking of all-purpose solutions, many times, growth can come by focusing on use cases specific to a section of your target audience and building a tool for them.

The Outlook toolbar allowed users to create a contact easily (at that time, users had to manually enter the contact details in a form to build their contact book). Since I never tried to build a contact list during that time, the whole concept seems bizarre to me but apparently it worked.

According to LinkedIn’s Series B deck, this toolbar feature contributed about 10% of overall email addresses uploaded on LinkedIn at that time.

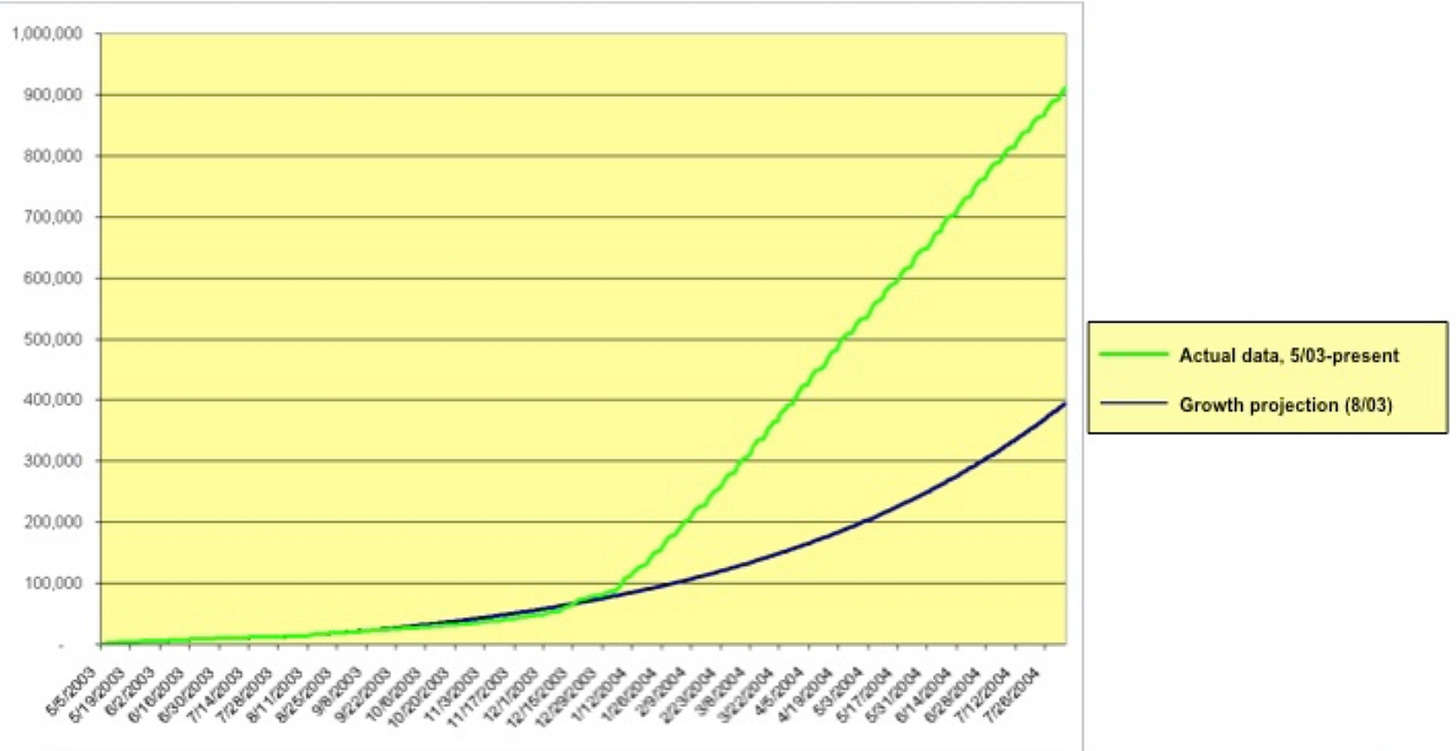

An overview of LinkedIn’s growth post-launch:

1 month: 4500 users

5 months: 40,000 users

7 months: 80,000 users

This is almost 100% MoM growth in its initial days. While this is impressive, in comparison, Instagram got to 1mn users in 2 months (a feat which LinkedIn took more than a year to achieve)

Take a look at their initial growth rate (also notice the sharp change in slope in 2004)

Also, note that this aggressive strategy also led to a lawsuit filed against LinkedIn at a later stage. It had to make a settlement of $13mn for unwanted and repeated emails.

Takeaways

Adding “urgency” to your referral invites, boosts the acceptance rate.

Figure out which existing (and preferably niche) platform/tool already has your target users and build utilities for those platforms. Most companies go after general purpose growth channels. Doing what everyone is already doing is a pretty tough way of achieving growth.

Other interesting reads w.r.t. LinkedIn

Give this Slideshare a read where Chris Saccheri (one of the founding team members) talks about early days of LinkedIn

LinkedIn’s Series B deck along with Reid’s advice on how to go about the pitching process. One of the best resources I have found on how to create a pitch deck btw.